Home

About Us

Allotments

Garden Equipment

Seed Suppliers

Manure Problems

Children's Pages

GLA Blog

Weather Blog

School Veg Patch

Useful Links

Honey Bee and Bumble Bee

There has been much in the news about fears that the bee population is in serious decline. Bee keepers comment that hives often resemble the Marie Celeste. Lord Rooker a minister from DEFRA has been reported as saying that the honey bee may become extinct within the next ten years.

Why the decline?

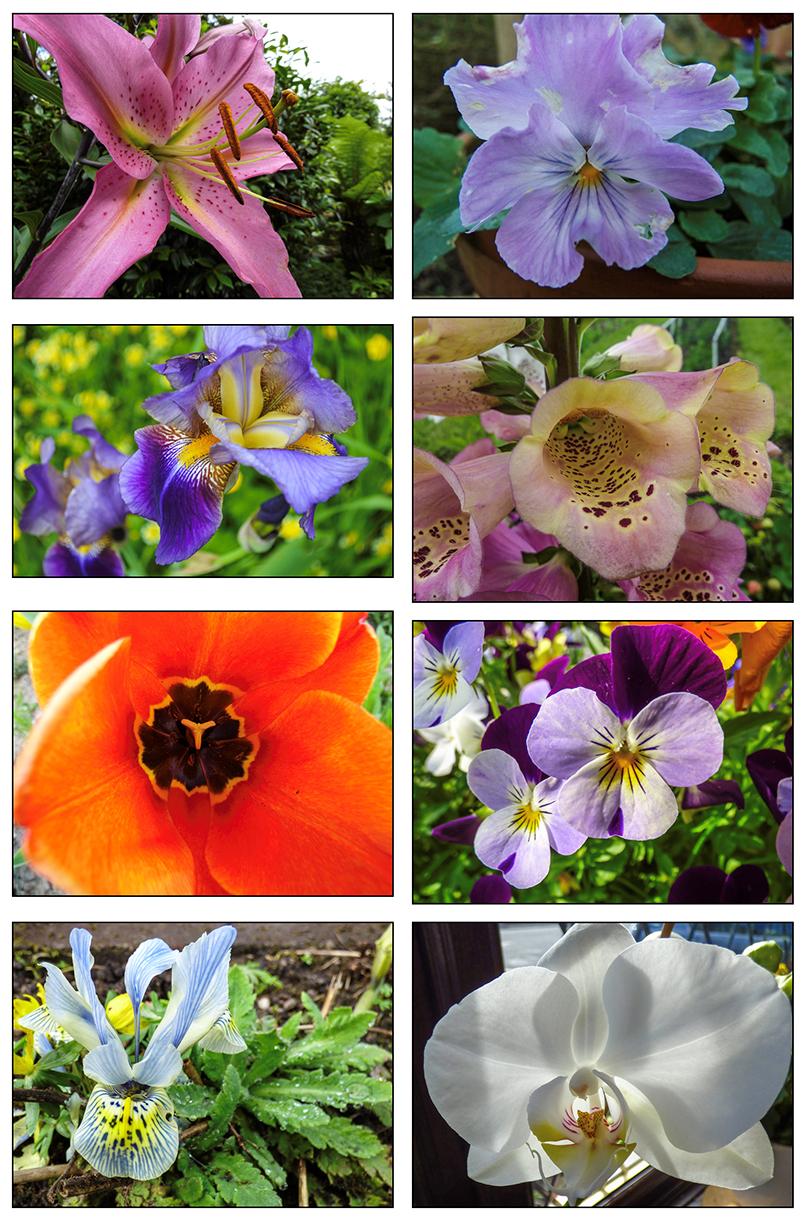

One problem for the bees has been the miserable wet weather over some summers prevents them from foraging successfully. Bees are also suffering from a loss of their food supply. They feed from flowers which are rich in nectar.

Although we still have flowers in our gardens – many of these will not provide the nectar that a bee requires. The double flowered varieties loved by some gardeners are not useful to the bees as they have difficulty accessing any nectar that may be present. Some choice ornamental plants have little pollen. When at Chelsea and other garden shows green was the ‘in’ colour – gardeners are increasingly growing plants for foliage rather than flowers. No flowers means no food for the bees! The loss of wild flowers in the countryside and use of pesticides and herbicides have had serious impact on the bee population. Bee disease and parasites are also suspected for the high losses. Being under stress bees more readily succumb to disease and the effects of parasite infestation. If all that wasn’t enough, the honey bee population is under threat from a foreign invader – the Asian hornet which preys on honey bee hives.

A contributory factor has been shown to be the use of pesticides containing neonicotinoids.

So should we be bothered?

The consequence of the decline in the bee population is not just a case of running out of locally produced honey. Bees are responsible for a large proportion of the pollination of flowers, fruits and other crops. In so doing they make a massive contribution to our economy. One estimate is that bees contribute £165 million to agriculture by pollinating plants that provide a third of the food we eat.

Without bees gardeners would lose some of their favourite varieties of flowers which are exclusively pollinated by bees. No pollination means no seeds from which to propagate new plants.

Many other products also include the use of beeswax in their production.

Summer wouldn’t really be summer without the buzz of the bees.

Some report that Albert Einstein said "If the bee disappears from the surface of the earth, man would have no more than four years to live." Others say that this quote was never uttered by Einstein but whether it was or not is irrelevant. The loss of our bee population would have serious implication for us all.

How can we help bees?

We can help the bees by cultivating plants that are rich in nectar and provide the bees with a much needed food supply click here for one suggested list and here for another. Plants that we have noticed, on our plot and in the garden, which are usually covered by visiting bees are globe artichoke, cardoon, sunflower, hebe, foxglove, comfrey and of course buddleias. The bees require a sequence of flowers to be planted that will see them through the season so when choosing what to plant it is important to consider flowering times and provide a range of plants. Red flowers are less attractive to bees as to them this colour is invisible.

We can avoid the use of pesticides many of which are poisonous to beneficial insects.

We can create or buy habitats in which bees can hibernate or set up home. This is appropriate for some bees but not for honey bees that need more specialised housing. Some bees prefer to build their nests underground. We found many nesting under a pile of straw that we had used to cover our dahlia plants over winter. The bees had chopped the straw into small pieces. The ground was literally buzzing so we just left the straw in place until the bees left. The dahlias grew through the straw so both plant and bee were happy

Bees in gemeral

Both male and female bees visit flowers but it is only the females that collect pollen and nectar to take back to the nest. The female of many species of bees has pollen baskets on her back pair of legs. As the name suggests these are used by the bee to carry pollen. As the bee visits a flower, pollen is caught on its body and it uses its legs to scrape as much of the pollen as it can into the baskets which are often to be seen bulging with yellow pollen. A bee can carry up to about a sixth of its body weight in pollen. Not all the pollen is successfully collected and some remains attached to the bees body to be deposited on the next flower that is visited and thus pollination occurs. Generally on a sortie the bee will gather pollen from only one type of flower which also aids effective pollination.

Besides collecting pollen the bee sucks up sweet sticky nectar which the flower produces in its nectaries. The bees suck up the nectar using a long straw like mouth-part. The mouth-parts or tongues are different lengths in different types of bees. The tongue length directly relates to the type of flower that each type of bee needs to browse. Bees with short tongues will browse daisy like flowers whereas those with long tongues can gather nectar from flowers such as honeysuckle.

Many flowers have special markings called honeyguides to direct the bees to where the nectaries are situated. These are a bit like the markings at an airport that guide the aeroplanes in when landing.

Some honeyguides are clearly visible to us in the form of spots, streaks and stripes, others reflect only ultraviolet light, and can be seen by many insects but are invisible to us.

As with other flying insects the buzzing sound is caused by the speed at which the insects beat their wings, something like 180 beats a second!Unlike the wasp that builds its nest from a type of papier-maché, the bee constructs her nest from wax which she produces from her abdomen.

The honey bee

The honey bee isn’t actually a native of the UK, it was introduced into the country from southern Asia to provide honey, however it has more than enough paid its way in the work that it does with respect to pollination.

In a mature colony there may be more than 50,000 individuals. The majority of colonies of honey bees live in hives maintained by beekeepers. Each colony has one large female bee – the queen bee. Her sole responsibility is to lay eggs. Other than that all the other work is carried out by the workers who are also her ‘children’ in fact her ‘daughters’. They build the comb, keep the hive clean and feed and protect the grubs and the queen.

The young nurse bees produce a substance called royal jelly. Unlike the majority of larva, which are fed a small amount of this, those destined to become the queens, are fed exclusively on this substance. The queen bees continue to feed on this substance for the rest of their lives.

As is the case for most social insects only a few males are produced in late summer. Their role is to mate with the newly born queens. The young queen will mate with as many males (drones) from other colonies as she can. The males must come from a different colony to ensure that the new queen forms a healthy colony. To ensure that bees from the same nest do not mate, the males usually hatch and leave the nest before the females.

Honey bee colonies are very efficient and highly organised ‘societies’. If a honey bee finds a good supply of nectar she will give directions to the others using a series of dance moves so that they can locate the area and join her on a browsing foray.

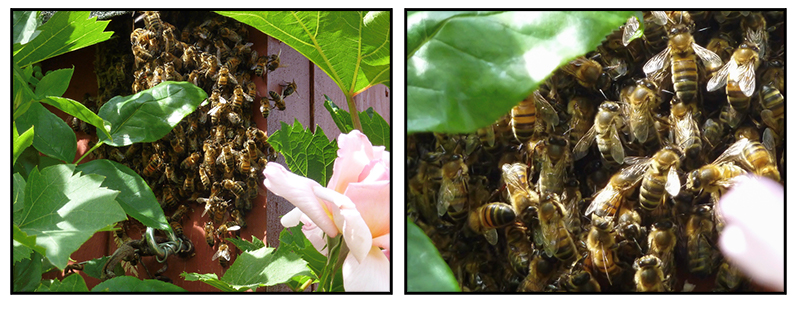

If bees feel that the hive is becoming too over-crowded the queen leaves the nest taking a large number of her workers with her. This mass exit of the hive produces what we call a swarm of bees. The swarm is looking for a new hive and will usually come to rest in a tree whilst some of the workers search for a suitable new site. In fact it is usually the bee-keeper who removes them to an empty hive. Back at the old hive a new queen is produced to take over the old queen’s duties. The swarm of bees in the video above had come to rest on a fellow plot-holders shed.

Honey bees are inactive during the winter and stay in the hive, honey is stored to see them through the months when food is unavailable. Where honey is taken from the hive, a beekeeper, will substitute this with a sugary substance. During winter the honey bees gather in a tight cluster. Those in the centre of the cluster feed from the honey and generate heat which keeps the rest of the cluster warm enough to survive extremely low temperatures. The queen remains in the centre of the cluster but the others shuffle around and take turns to be in the middle.

The sting of a honey bee has barbs. This means that if she stings a mammal – like us for instance – she is unable to pull the sting out. Our skin is too elastic and clings to the sting. If the bee tries too hard the sting will be pulled out of her body resulting in her death. The bee isn’t an aggressive creature and doesn’t readily sting which is lucky for both us and them.

The bumble bee

There were once around 20 species of bumble bee found in Britain but some sadly are now extinct and several more are endangered.

Some are far more common than others click here for help with identification. Bumble bees are hairier than the honey bee. Large young bumble bee queens hibernate during winter but, unlike the honey bee, the rest of the colony dies. This means the bumble bee doesn’t store food for winter. After hibernation the queen spends some time feeding. She then looks out for a suitable nesting site. Sometimes this is underground, often in an old mouse nest or in leaf litter or long grass. Once she has found a suitable site the queen will begin to build the nest. The nest is constructed from a wax that the queen produces from her abdomen. The queen will construct a wax cell which she partly fills with pollen. She will then lay eggs in the cell and seal it using more wax. The queen then creates a similar cell which she fills with honey. This honey pot provides food for her and the developing grubs. The young queen sits on her nest of eggs, just as a bird does, to incubate them and keep them warm. Once the eggs hatch the queen will break open the nursery cell and feeds the grubs with honey and pollen. The grubs pupate and adult female worker bees emerge. From that point on the only task for the queen is to lay eggs whilst, as with other social insects, the workers collect food, and feed and raise the young.

After a time, around June, a number of grubs are fed with extra food. These grubs are destined to become the new queens. At the same time the queen lays some eggs that will develop into males whose only task is to fertilise the females. Once these special bees leave the nest the males and females find a mate, from a different nest. After mating the male dies. The young queens are the only bumble bees to make it through the winter. They feed themselves up and search for a winter resting place where they can hibernate. Once the young queens and males leave the nest the old colony has no more purpose and will survive for only a short time before all the bees die.

When she leaves her hiding place in spring the queen will search for a new, clean nesting site never returning to her old nest.

Unlike a honey bee, a bumble bee has no barbs on its sting and so can sting more than once. Like the honey bee, however, the bumble bee will rarely attack as it is just too preoccupied with getting on with its life to bother about us. As is the case for other bees and wasps the male has no sting.

Although this article features the honey bee and bumble bee, these are not the only types of bee common in the UK.

To view our homemade bee nesting block click here

For more information about the plight of the honeybee and how you can help visit the Soil Association website

Our Plot at Green Lane Allotments Blog | A Gardener's Weather Diary | School Vegetable Patch Website

© Our Plot on Green Lane Allotments - Please email me if you wish to use any of this site's content