Home

About Us

Allotments

Garden Equipment

Seed Suppliers

Manure Problems

Children's Pages

GLA Blog

Weather Blog

School Veg Patch

Useful Links

Ladybird

Ladybirds aren’t always ladies and certainly aren’t birds!

Ladybirds are so named as in the Middle Ages they were known as the beetle of Our Lady. This was because in religious paintings the Virgin Mary was then portrayed as wearing a red cloak. That explains the lady part but I’m not sure where the bird bit comes from! In America ladybirds are referred to as ladybugs – but they aren’t bugs either! They are a species of beetle

Most people who become rather squeamish when coming face to face with a beetle will happily allow a lady bird to crawl over their hand. I wonder if they realise that a ladybird is a beetle too. Maybe they do but are happier if the beetle is brightly coloured and ‘friendly’ looking! Although ladybirds seem harmless, they can deliver a ‘gentle’ bite if they feel threatened. They are certainly neither gentle nor friendly as far as aphids (greenfly) are concerned!

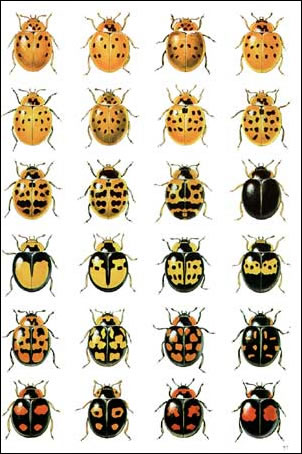

Most of us if asked would say that a ladybird is red and has black spots, however there are 40 species of ladybird resident to the UK and not all are red and not all have spots!

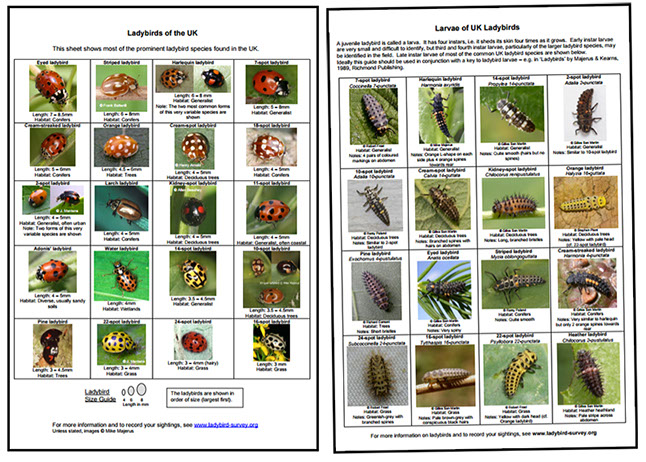

Click on the image below from http://www.ladybird-survey.org/ to view some of the species found in the UK.

You will see from the chart, that ladybirds are also black, orange, brown or yellow and have white, red or black spots.

The number of spots also varies. In fact many ladybirds are named according to the number of spots that they have. The eyed ladybird has black spots, each with a sort of yellowish halo – a little like a leopards spots. Although the seven spot ladybird used to be the one we see most often in our garden and on our plot, (before the Harlequin ladybird came along), we do see other species, some of which are shown below.

The ladybird on the right is a 10 spot ladybird and was found on a blackcurrant bush. It is called a 10 spot but can have any number of spots from 0 - 15 and can also be a variety of colours. I think that the one on the left is also a 10 spot. The one on the middle left is a cream spotted ladybird that was photographed on our apple trees.

The red part of the ladybird is made up of a pair of hard wing cases that protect the flimsier wings which are folded neatly inside the wing cases when not in use. Everyone must have seen the ladybird open up the wing cases and unfold their wings when preparing to fly.

The wing case or carapace also protects the ladybird’s head which it retracts a bit like a tortoise.

Ladybirds are regularly seen anywhere where there are plenty of green plants such as gardens, woodlands, hedgerows and fields. Most ladybirds feed off aphids and other small insects such as spider mites or mealy bugs, so should be considered as the gardeners’ friends. They will also eat the whitefly that we have been plagued with this year – that is if they can catch them! One or two ladybirds are vegetarian and eat mildew and fungi and so are also beneficial to our plants.

It seems that a ladybird in search of a mate doesn’t discriminate between species. As can be seen from the photo below ladybirds don't always mate with their own kind. Does a cross species result in offspring and if so are hybrids produced?

After some energetic mating.

Ladybirds lay long thin yellow eggs in clusters under the leaves of plants such as nettles or other plants with a plentiful supply of food for the hatched larvae. This means that the eggs are protected from the worst of the rain. After about a week the eggs hatch. The young or larvae don’t look anything like the adult ladybird and, like most other insect larvae, spend all their time eating and growing.

This period of their lives lasts about three weeks, during which time the larvae eat several hundred aphids. They then turn into a chrysalis and about a week later the adult ladybird emerges.

Pupa of native ladybird

Larva and pupa of a Harlequin ladybird

During winter ladybirds go into diapause (a sort of hibernation) and will hide in cracks and crevices, sometimes in quite large numbers. Some even find their way into houses.

Ladybirds can live for up to a year.

As in most brightly coloured insects, the colouring of the ladybird acts as a defence system to warn birds not to eat them. Apparently the ladybird tastes very unpleasant when eaten and birds soon learn to leave them alone. When a ladybird feels threatened it will release a foul smelling yellow liquid from its joints. The liquid is ladybird blood and will stain anything that it comes into contact with. When attacked ladybirds will also play dead by folding their legs and antennae under their wing case and keeping very still.

The biggest killers of ladybirds are fungi, parasitic wasps, spiders and ants. Some birds such as swifts and swallows also seem immune to the chemicals exuded by ladybirds, however numbers are mainly controlled by the availability of food. So more greenfly should mean more ladybirds – that is if we can resist the urge to use chemical control.

So everything in the garden is rosy for our ladybirds, or is it ...?

Our native ladybirds, now face a major threat from another species – the harlequin ladybird. These ladybirds are native to Eastern Asia. Harlequin ladybirds are voracious feeders of aphids and other plant pests and so many countries introduced them as a biological control. Consequently the Harlequin established itself in many parts of Europe and North America.

Harlequin ladybirds are larger than our native species and can often be recognised by a marking in the shape of a letter M just behind their head.

In 2004 the first harlequins were found in Britain. This species is larger than our native ladybirds. It consumes more food, has a more varied diet and a longer period in which it produces offspring. Harlequin larvae have been found as late in the year as October. Harlequin larva are more spiky than their British cousins.

For reasons given above it is unlikely that native ladybirds will be able to successfully compete with harlequins. Harlequins will also turn cannibalistic if food is in short supply and will also eat other beneficial insects such as lacewing.

Many gardeners may think that if the harlequins eat more aphids they should be welcomed into the country, however these ladybirds can pose a nuisance to humans too.

During autumn and winter, harlequins tend to make their way into our homes in large numbers. There have been recent reports on the television of the serious consequences of this. Often the warmer temperature inside our homes encourage the harlequins to continue breeding – after all these creatures do originate from much colder climates than ours - and the numbers sharing our living spaces dramatically increase. Not only do large numbers of harlequins make life unpleasant but they also cause damage by permanently staining carpets and curtains etc with the yellow blood which they excrete. If harlequins fail to find food in our homes they will also bite humans.

Harlequins also cause damage in the garden by sucking on soft fruits. Apparently they are particular fond of grapes which makes them a major problem in vineyards.

The movement of harlequin ladybirds is being closely monitored as is the effect that they are having on our native insects. To read how you can help click on the image above to visit the Harlequin Ladybird Survey Site

Our Plot at Green Lane Allotments Blog | A Gardener's Weather Diary | School Vegetable Patch Website

© Our Plot on Green Lane Allotments - Please email me if you wish to use any of this site's content